History & Heritage

Our home county of Somerset teems with nature, history and legend. One of the area’s most fantastical claims to fame is as the last resting place of King Arthur (Glastonbury Tor), while there is no doubt that Alfred the Great hid in Somerset from the Vikings where he planned his next (victorious) battle.

Many of these stories, whether fact or fiction, take inspiration from the unique qualities of Somerset’s landscape; a tapestry of grasslands, meadows, woods, orchards and coastline.

The Gravity site as the former base of Royal Ordnance Factory 37 has no less an extraordinary story to tell.

Below we explore Gravity’s industrial and social heritage and that of our closest neighbouring town, Bridgwater, along with the wealth of natural capital the region offers.

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)

Located in the low rolling Polden Hills, between the Mendip Hills and Quantock Hills (both an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) and close to Exmoor National Park, Gravity occupies a very special place.

ROF 37: An enduring legacy

Our nearest town Bridgwater is a source of inspiration for how Gravity is taking shape. Sedgemoor District Council has shaped a Bridgwater Vision and has pledged that by 2060, Bridgwater will 'be an energy conscious town known for its ambitious approach to sustainability and low carbon living'. This is the bold vision of a town with a long history of industrial endeavour, and the ability to adapt to change.

Royal Ordnance Factory 37, the factory formerly based at Gravity, was in operation for 67 years, becoming an integral part of people’s lives in the surrounding villages and towns.

Opened in 1941, at the height of its production over 2,800 people were employed on the site ranging from chemists and technicians to office, security and canteen staff. Generations of local families worked at the plant, and its social centre Club 37, which still thrives today as a community hub, was at the heart of it all.

At the outbreak of World War Two, the government had chosen the site as the ideal location for a Royal Ordnance factory, which needed around 4.5 million gallons of water each day.

Airey homes – prefabricated houses – were produced at the plant in response to the urgent need to replace homes that had been destroyed during the Blitz of 1940 and 1941.

After the war, manufacture turned to the production of materials for the plastics industry. In 1987, the government sold the factory to BAE which continued manufacturing until the site was decommissioned in 2008.

Club 37 remains at the heart of local life and represents an enduring link to the site’s extraordinary past. We are celebrating this legacy, and taking inspiration from it, as we look to position the Gravity site once more as a place to grow careers, create new opportunities and bring people together.

Gravity is supporting The South West Heritage Trust in a range of projects to create a living historical record of what it was like to work at the site.

Click here for more information and to watch ‘Our Lives at ROF 37’ – a film featuring interviews with the people who worked there.

Bridgwater

A strategic site

Straddling either side of the River Parrett, the place we now know as Bridgwater attracted the attention of the Normans in the 11th century as a strategic site for a castle. Two hundred years later, the Norman structure was used to form the foundations of Bridgwater Castle, complete with a tidal moat and a ‘watergate’, which controlled access to the town’s quay.

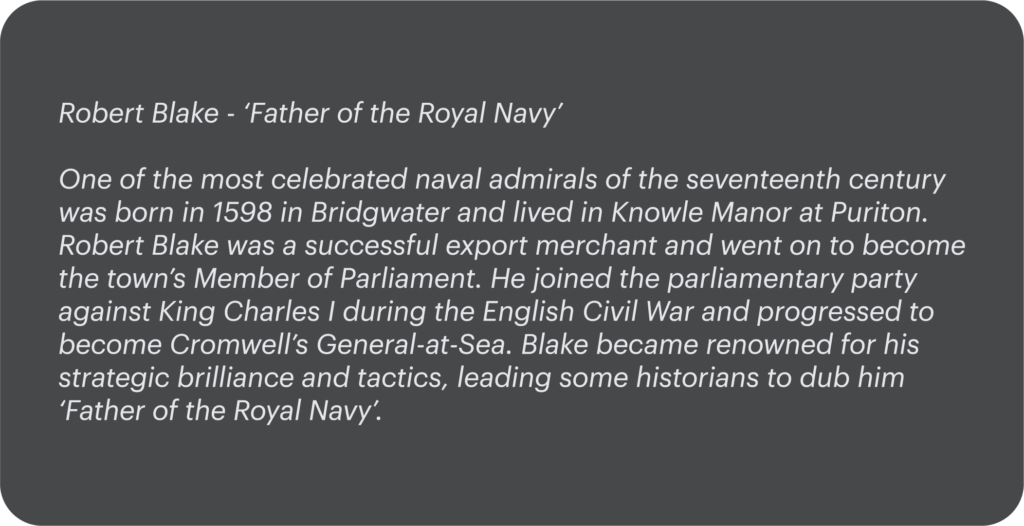

Bridgwater Castle, which would eventually be destroyed by Cromwell’s army in 17th century, unlocked Bridgwater’s potential to become a busy inland port (until the river silted up too much) and a trading centre, leading to its present-day character as a lively market town.

Growth as a port

From the 15th to 18th centuries, the cloth trade was the mainstay of the town’s prosperity, with woollen cloth from Somerset exported around the world. The town’s busy quay and riverscape was characterised by the tall masts of schooners and ketches.

But the industrial revolution moved the centre of commercial and industrial activity northward towards Bristol, bringing about a period of decline.

Reinvention

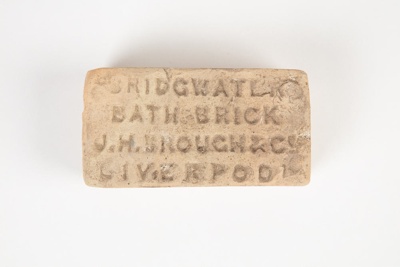

During the 19th century, the town found a new identity as a centre for manufacturing roofing tiles and bricks. ‘Bath bricks’ were manufactured from 1823 from local silt and exported to Europe, the Middle East, America and China.

By 1861, eight million bricks were being manufactured per annum, increasing to 17 million by 1900. However, the development of alternatives, depletion of manpower and the disruption to exports during World War I eventually led to the industry’s decline.

It was during the 19th century (1871) that the unusual ‘telescopic’ bridge over the river near Barham’s Brickyard was built and remains to this day. The late 19th century also saw Bridgwater’s already well-established carnival tradition ‘modernised’ with the use of gas lamps.

For a time, the arrival of the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal in 1827 was a game changer. It enabled coal from South Wales to be distributed by barges inland with Bridgwater acting as a trade hub. Trade expanded further with the construction of Bridgwater Docks in 1841 and the subsequent development by the Bristol and Exeter Railway of the wharves and sidings at the nearby village of Dunball. But the opening of the Severn Tunnel in 1886 led to the decline of shipping as the use of rail waggons increased.

Diversification

In the early 20th century, Bridgwater saw the launch of a home-grown motor car company. The Bridgwater Motor Company started production in 1905, with facilities so impressive by the day’s standard that The New York Times dubbed it ‘one of the most modern garages in the country’. The business made 12 machines and ceased production in 1908.

The railway station was built to the east of the town and encouraged growth away from the river, and a more diverse range of companies to look to Bridgwater as a base. In 1937, Cellophane opened a factory that went on to be a major employer in the town until the factory’s closure in 2005.

Although the local brick and tile industry declined during the 20th century, the ready supply of these materials was another reason the government chose the area for the location of ROF 37.

A growth town

Since 1974 Bridgwater has been the administrative centre of the District of Sedgemoor. Its industrial base has diversified further, and its annual November carnival has become a major cultural event attracting around 150,000 people. The town’s population has swelled from about 15,000 at the beginning of the 20th century to over 41,000 today and that growth is projected to continue.

In 2018, construction work started on Hinkley Point C – a £20 billion, twin-reactor station eight miles from Bridgwater. It is the first new nuclear power station to be built in the UK for more than 20 years and is set to create 25,000 jobs during construction. This will bring a multitude of new opportunities to Bridgwater and the surrounding area. When built, there will be about 900 jobs at Hinkley Point C.

Gravity aims to build on these opportunities, providing a legacy and an onwards career path for those currently involved in the construction of the station once it is completed in 2025. By providing a home for businesses making a difference socially, economically and environmentally, we will support Bridgwater’s vision of becoming a low carbon town with a focus on sustainability.

Natural Heritage

Gravity’s location places us within the very heart of Somerset; at the gateway to Exmoor National Park, and between the Mendip Hills and Quantock Hills. There are thirteen national nature reserves in the county, many of which are internationally important for migrating birds.

Managing the landscape

Somerset’s environment has had careful stewardship since before the Domesday Book. In the Middle Ages, the monasteries of Glastonbury, Athelney and Muchelney were responsible for management of the natural landscape.

In order to harness water for manufacturing at ROF 37, engineers created the Huntspill River; a straight, five-mile channel fed by the River Parrett. The King’s Sedgemoor Drain, an existing artificial drainage channel, was also widened to help supply water to the factory. Both these waterways are now an integral part of the area’s water management system, acting as drainage channels as well as reservoirs.

Sustainable water management will be a key feature of the Gravity regeneration approach to ensure we harness and optimise natural resources as well as consider how we can introduce new opportunities for leisure.

A haven for native and International wildlife

Gravity's home county of Somerset has 13 national nature reserves of both national and international importance, supporting a vast variety of plant and bird species. The county also counts 32 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), of which 12 are also Special Protection Areas.

West Sedgemoor is a SSSI where, as well as having the largest lowland population of breeding wading birds, water voles and otters breed too. At Ham Wall you can witness one of nature's spectacles - vast flocks or murmurations of starlings congregating and swirling in the winter evening skies before settling down to roost.

Somerset's Natural Capital

These natural assets support a rich range of leisure activities from bird watching and walking, to cycling and rock climbing. In addition to offering enjoyable experiences for the community, Somerset's natural heritage also offers strategic opportunities for investors and businesses.

As an Enterprise Zone, Gravity will seek to reinvest business rates into its local landscape, leisure and wellbeing opportunities; investing in Somerset's natural capital as part of our commitment to supporting a green recovery. We will support our partners to progress initiatives for landscape recovery and land management schemes that aim to improve biodiversity and combat climate change, with the community at its heart.